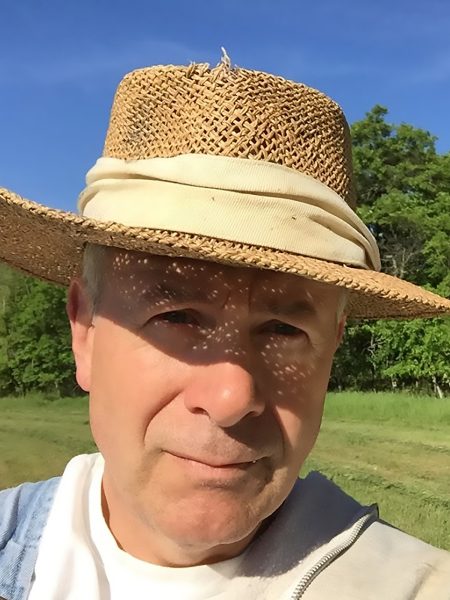

The sound of winter

February 6, 2022

If below-zero temperatures had a sound, it would be this: the clang of an iron maul striking the frozen apron of a manure spreader.

Our recent cold snap — we dipped close to 30 below zero in my neck of the woods — made me reflect on memories of milking cows and doing chores during the bitter weather. It seemed like every routine task became much harder in the cold temperatures.

Chores — which included feeding calves and washing the milking machines — were sandwiched in between the daily milking at 5 a.m. and 5 p.m.

Cleaning the barn — the term that we used when we hauled manure — is an essential daily task in a stanchion barn like we had. The cows would be turned out to the outdoor feed bunk for a couple of hours, and we would try to clean the barn and bed the stalls as quickly as possible. If the task took too long, the water pipes in the barn would begin to freeze as the only source of heat we had in the barn was body warmth from the cattle.

Step 1 was to start the tractor, which had a block heater to keep it warm. Somedays a little extra help was needed from a blast heater and a battery charger. Step 2 was to crawl into the manure spreader with an iron bar or maul and pound on the aprons to make sure they w

ere not frozen. Starting the spreader without that step would risk breaking the chain and create a miserable repair job.

The same process was repeated to the links of chain exposed to the outside on the barn cleaner — a long system of chain and paddles that pulls manure through the gutter and dumps it into the manure spreader.

For many years our primary tractor did not have a cab, but rather a flimsy canvas apron with a plastic windshield that was installed ea

ch winter. Huddling down behind the windshield helped avoid freezing your face as you drove to the field to spread the manure. When the snow was too deep, we created a manure pile that was moved in the spring.

Running the spreader completely empty and scraping the sides was a critical step for the next day’s use. Any manure left in the spreader would freeze and create even more labor when pounding on the frozen chain.

The manure spreader would also be used to haul wood, as we often would drive into the woods during the winter seeking dead trees that could be cut, split and burned right away without seasoning.

Usually, one person would clean the barn while a second scraped and bedded the calf pens. Bales of hay were thrown down chutes and spread out for feeding and stacked for a nightly feeding as well.

If everything went well — and each day always had its challenges — the barn could be cleaned, bedded with straw or chopped corn stalks, and be ready for the cows to come back inside within a couple of hours. There was a break for lunch and then it was time to cut and split wood or fill the wood box.

The cows would be turned back outside to the feed bunk in the later afternoon and then brought back inside for the evening milking. We were usually done by 7 p.m.

The days of milking cows are long gone, but I still have a few animals to tend. And the weather struggle continued when our heated waterer froze — even though I made sure it was still working during the coldest of temperatures. But one cow, two donkeys and two goats didn’t drink enough to keep the water flowing.

So, it’s back to carrying 5-gallon pails — 182 steps uphill — for the foreseeable future or until it warms enough to thaw the waterer. And the well has been acting up, so I’ve been making a few more trips to the bottom of the cold cistern.

There is a bright side.

Meteorological winter is now two-thirds complete.

The days are growing longer.

As my memory recalls, it could be worse.