Feb. 19, 2014

By Vesna Brajkovic

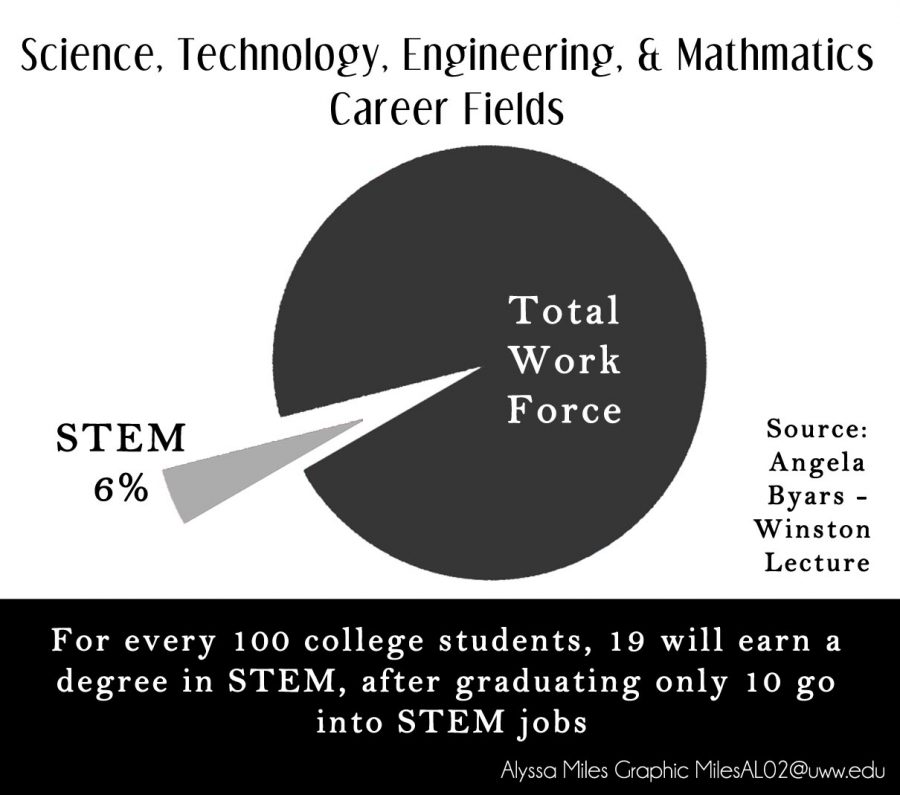

When a room almost half full of UW-Whitewater students was asked to raise their hands if they are majoring in the science or engineering field, less than five raised their hands.

Angela Byars-Winston asked the quesiton on Feb. 13 as a part of the African American Heritage Lecture Series.

Byars-Winston is a counseling psychologist and associate professor in the department of medicine and public health at UW-Whitewater.

The small show of hands prompted her to say this “represents the percentage of folks nationally” who also major in these fields.

“Developing the Next Generation of Culturally Diverse Scientists and Engineers,” Byars-Winston’s lecture focused mainly on understanding cultural influences on academic and career development for students of minority in the science, technology, engineering and mathematics (STEM) fields.

Devon Winfrey, a senior biology major who introduced Byars-Winston, was one of the few people with his hand raised.

As a young black student majoring in a STEM field, Winfrey exemplified the type of rare student Byars-Winston was trying to encourage others to use as an example.

“Out of four of my classes in the STEM field, I can only think of two other African-American students that are in class with me,” Wilfred said.

According to Byars-Winston’s lecture, that’s the issue and the reason she wants to promote STEM pursuits. She said the decrease in interest or completion of majors within these fields, which has largely been dominated by white males, is harmful to an overall diverse growth of the fields.

As an expert in career

development and chosen as a Champion of Change by the White House in 2011 through President Obama’s Winning the Future initiative for her research efforts, Byars-Winston emphasized the importance of the STEM fields.

“STEM occupations only account for about six percent of the U.S labor market, but 50 percent or more of the growth in the economic development comes from STEM fields,” Byars-Winston said.

She said students just don’t see themselves as scientists, and to change there needs to be “more exposure.” Being more “deliberate” with how the demographic looks could help. When adding and supplementing examples in classes, Byars-Winston said that adding gender, ethnic, and race diversity to the mix could make a big difference.

“It just means that we have to be more creative of instructors and faculty members, Byars-Winston said. “I think for students, having access to people, like Devon [Winfrey], helps them realize that these people, they’re not aliens.”

David Travis, dean of the College of Letters and Sciences, gave his closing remarks on the lecture, recalling that throughout his years on campus he has seen the diversity improve greatly, but the journey is not over yet.

“The progress that we’ve made is not good enough to satisfy me yet, but I’m really optimistic,” Travis said. “The university is really committed to [improving diversity].”

“Although this may not be a direct correlation” from 2001-2010, which is the latest data they have four-year graduation data for, “the number of females graduating in the STEM fields went up by 30 percent, and the number of minorities, specifically African-Americans and Hispanics, increased by 60 percent.”