This semester, students in the Islamic art class are learning about specific kinds of Middle Eastern art that have played a significant role throughout history. At the beginning of the semester, students were asked to pick a particular artifact and research it. They then uploaded their findings to Wikipedia.

The goal of the class is to discover what Islamic art truly is because it has many different meanings.

“One working definition that we often use is any art made by Muslims, for Muslims, or in Muslim majority cultures,” lecturer Ashley Dimmig said. “That could include Jewish craftsmen working in the Safavid Empire in Iran in the 1600s. You don’t have to be Muslim but in some way tied to the religion or culture of Islam.”

With a small class size, only four groups presented. The groups gave their presentations over the course of two class periods, which allowed for plenty of time for discussion.

The first two presentations were about Qajar Lacquer and the calligraphy of Mohamed Zakariya. In short, Qajar Lacquer refers to Persian illustrations of literary scenes during the Qajar dynasty. These illustrations can be uses portraits or appear on items such as boxes.

“It’s about someone who’s currently alive and I guess it adds a human factor. He helped revive Ottoman calligraphy specifically,” student Henry Hubler said of Zakariya’s work.

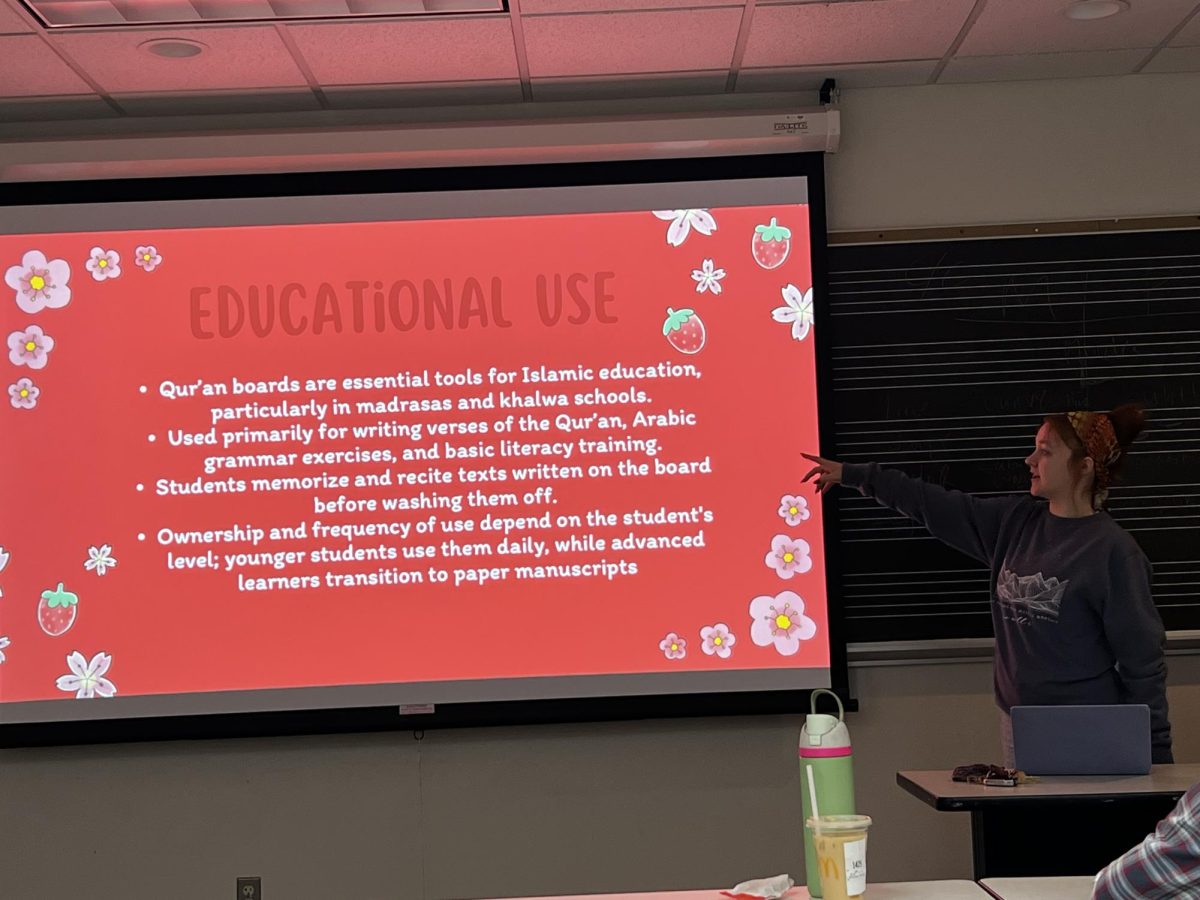

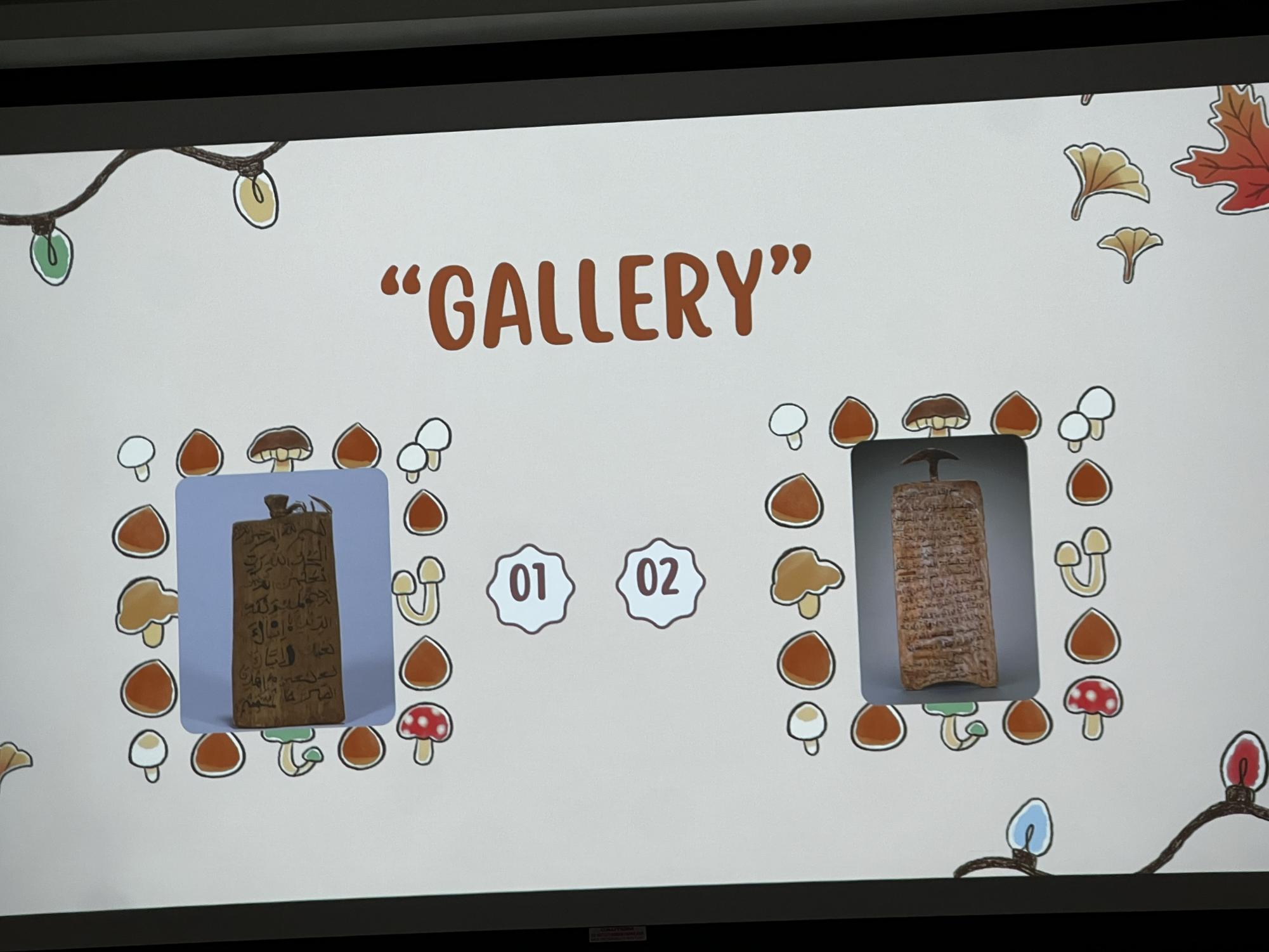

In the next class period, the two topics were African Qur’an boards and Ottoman tents.

Qur’an boards are wooden tablets for Islamic education in West and sub-Saharan Africa. They are also religious artifacts that played a role in ritualistic practices and spiritual healing. Students would recite texts on these boards and memorize them before washing them off. A reason these were almost lost to history was due to it being too far geographically from the Middle East and not culturally in tune with most of West Africa.

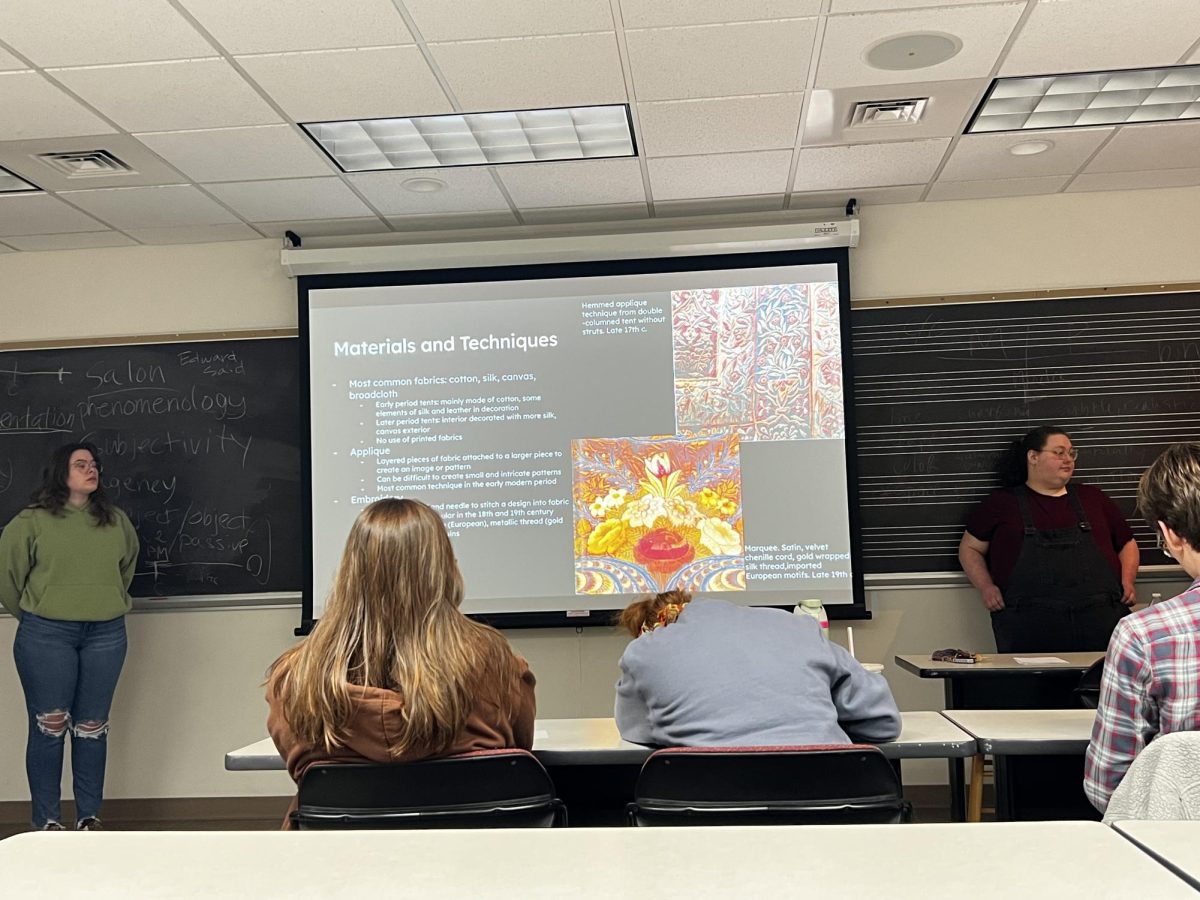

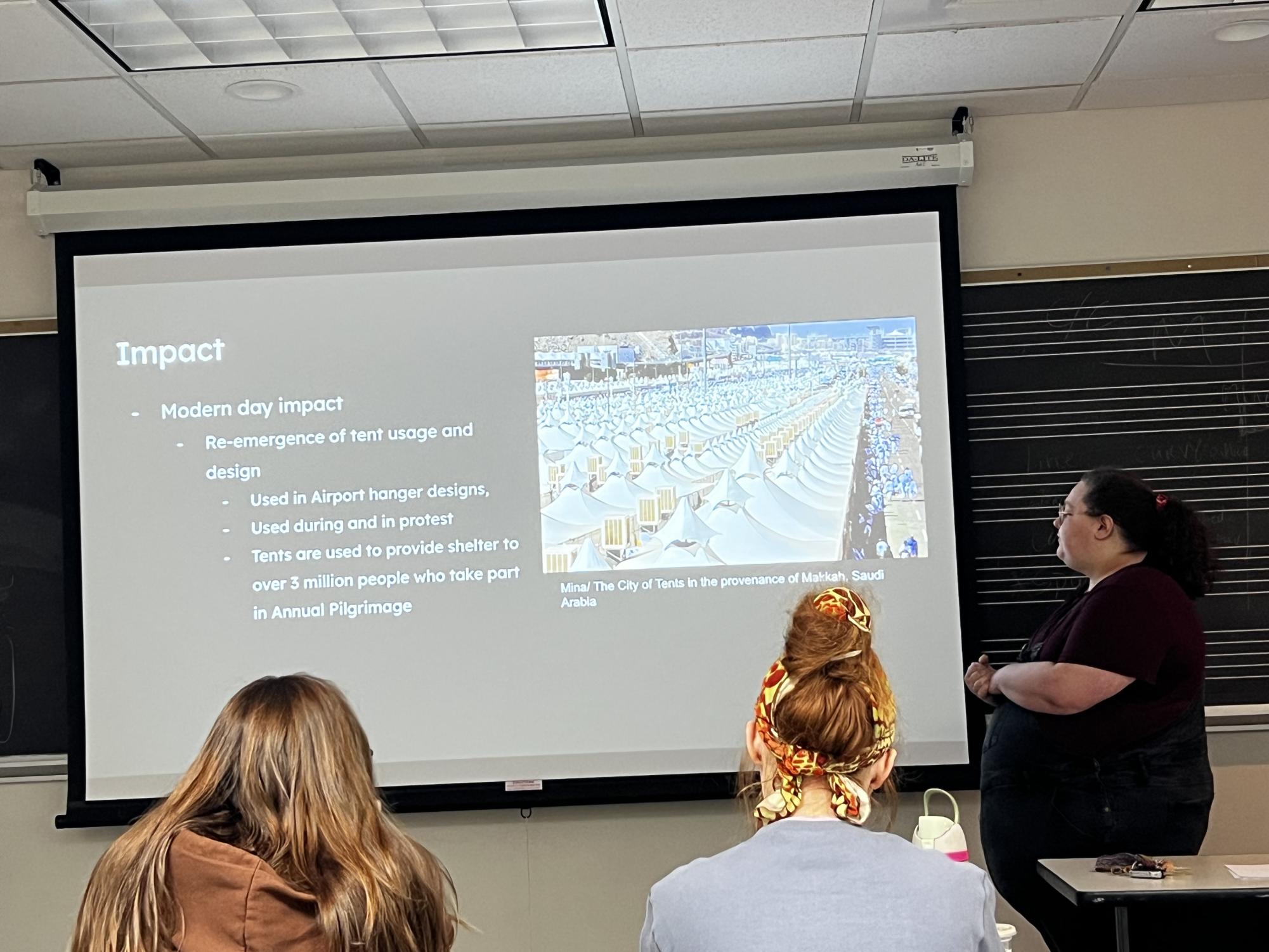

Meanwhile, Ottoman tents were used as a convenient way to rest overnight in their mission to spread the Ottoman Empire. They were made of cotton, silk, canvas and broadcloth and commonly used colors like red, blue, green and yellow ochre. They had beautiful interior designs and had the versatility to host military strategies, weddings and religious events, and even placed in tough climates including mountain ranges, forests and deserts. They were used from the 14th century all the way to the 19th century.

Since there’s minimal information about these various crafts online, Hubler explained the most difficult part of his research on Zakariya’s calligraphy.

“Taking a teacher lineage between students and teachers and that goes back hundreds of years. Trying to find a way to connect with his teachers who are from different backgrounds and have different styles of calligraphy and tracing that backward and seeing where all of that came from. Besides that, I don’t want to say it’s too difficult, just time-consuming,” Hubler said.

Dimmig’s background in this topic traces back to her senior year at the Kansas City Art Institute. She originally studied textiles broadly and got an internship at the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art where she was given Iranian textiles to research. That inspired her love for Islamic art and now she knows some Persian, Turkish and Arabic to decipher the basics of the Qur’an and other calligraphies.

This class is brand new to UW-Whitewater this semester.

“It’s important to think about things we’ve never thought about before. To look beyond ourselves and our own culture. I think part of what we’re doing here is expanding our worldview,” Dimmig said.

There’s only one other Islamic art historian in Wisconsin, her colleague at UW-Madison, so it’s a very niche field that not a lot of people study. She said that’s a perk of having her here, teaching this class and talking about her passion.

Halfway through the semester, these student presentations proved they’re showing genuine interest in Islamic art. Their uploads to Wikipedia will help them become more tech-savvy and cultured in a region systemically obscured by American schools.