The UW-Whitewater campus is home to numerous superstitions and legends. One of these is the cursed book.

For years, this book has been known as the haunted book in Anderson Library, its existence spreading far and wide across campus along with various rumors. Legends of curses, ghostly apparitions, and fatalities have captured people’s imaginations. Some claimed the book was written by a witch, believing that merely looking at it could cause one to fail exams or even lead to the death of a loved one. However, the truth is that no one has actually died after reading this book, and such a book does not truly exist.

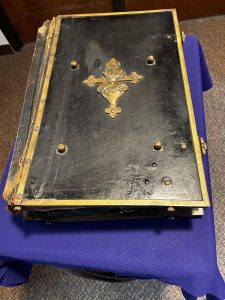

The book’s name is the “Graduale Cisterciense,” published in Belgium in 1899 by the Cistercian Order, an order of Catholic monks. The book contains Latin text and neumatic notation, giving it an eerie and mysterious feel. The cover features the Sacred Heart of Jesus, a common Catholic symbol placed atop a cross. A large brass lock, reminiscent of medieval manuscripts, secures the book, adding to its antique and ominous appearance. This book is quite rare. While other copies exist worldwide, it serves as an important example of monastic chant for researchers.

Superstitions also surround the name “Second Salem” in Whitewater, stemming from the Morris Pratt Institute and its geographical surroundings. Morris Pratt, a pioneer and successful businessman from New York State, migrated to Whitewater, Wisconsin in the 1840s. He converted to spiritualism after visiting the Lake Mills spiritualist center in 1851. To fulfill his pledge to donate to the spiritualist movement, he built one of the most expensive buildings in Whitewater, which became the Morris Pratt Institute.

However, due to fund losses from the Great Depression of the 1930s and declining student enrollment, it closed in 1932. It reopened in 1935 but ultimately closed again in 1938, with the building sold in 1946. The institute itself relocated to the Milwaukee area and continues to exist today.

Among the legends associated with Whitewater is Mary Worth. She is a legendary figure said to roam the cemetery grounds with an axe, seeking new victims, though most knowledge indicates there is no evidence such a person actually existed in Whitewater. Another legend is the Triangle Cemetery. This refers to the fact that Whitewater’s three cemeteries form an almost perfect isosceles triangle on a map, allegedly linked to black magic or Satan worship.

However, some practitioners of the occult dismiss its significance, arguing that any three points could form a triangle. There are also rumors about the Witch’s Tower. The water tank in Starin Park is called a place where witches perform rituals, and there’s a rumor that the barbed wire around the tower faces inward to trap evil spirits, not people.

Shalomi Sahabandhu, a student at the University of Wisconsin-Whitewater, said that the “witch tower in Starin Park has a lot of talk about ghost stories and like they used to be people saying how witches used to live here.”

Beyond this, there are tales of a complex underground tunnel network throughout the city, rumored to have been secret meeting places for witches. There’s also a rumor that the field where UW-Whitewater’s Wells Hall dormitory stands was once a gathering place for various magical groups and covens.

“The cemeteries we have by Ma’iingan, like people would always say it’s haunted, reveal her awareness of various superstitions on campus,” said Jennifer Motszko, head of archives and library associate director. “While many students aren’t aware of the book, those who are curious are welcome to visit the archives to see it. Most are more interested in learning the history of the book and the origin of its mythology than they are superstitious. Though few students are true believers in the myths, the book serves as a fun conversation piece during the spooky season.”

Since Whitewater’s legends contain diverse stories, grasping their deeper meanings and narratives rather than treating them as mere rumors will also help understanding Whitewater’s history.