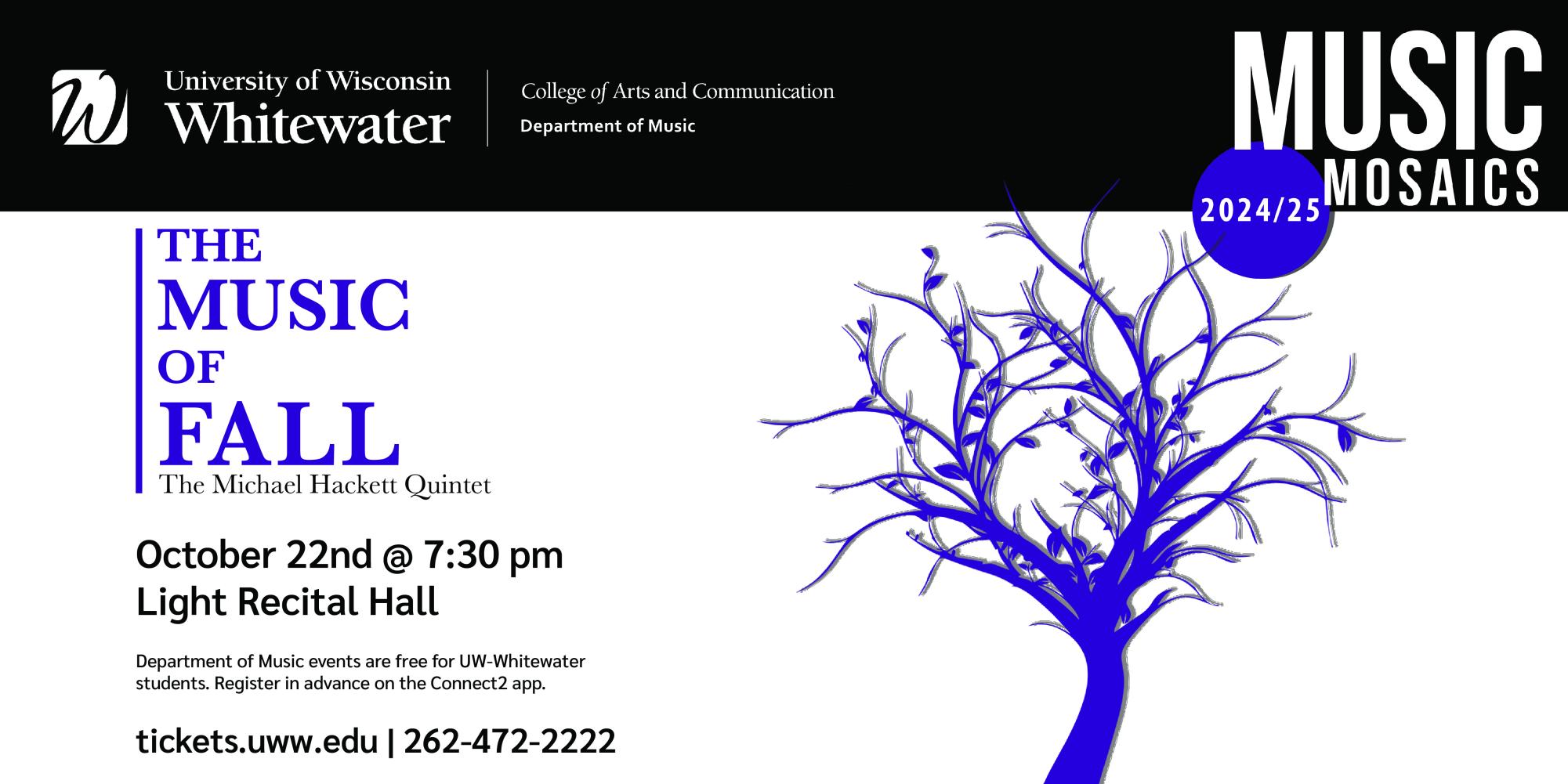

A tribute to bebop

Faculty Jazz Ensemble honors Charlie “Yardbird” Parker

UW-Whitewater Music Department Youtube

From left: Faculty Jazz Ensemble members Robert Hodson, Michael Hackett, Bradley Townsend, Devin Drobka and guest artist Sharel Cassity perform during a Music Mosaics Tribute to Charlie “Yardbird” Parker.

December 13, 2020

Charlie “Yardbird” Parker, Dizzy Gillespie and Earl Hines traveled the country during the swing era in the 1930’s. This was an era when radio had just caught on and music artists produced real physical records. When World War II began in the 1940’s, many served, but not Bird and Dizzy because of their societal beliefs.

The Faculty Jazz Ensemble pay tribute to Charlie “Yardbird” Parker Dec. 1 – 15 through a virtual concert in honor of what would have been the 100th birthday year of the Grammy Award-winning saxophonist.

“Bird was a heroin addict and Dizzy was a conscientious objector, and refused to go to war. His comment was, ‘Why would a Black man fight for a country that treats me like a non-citizen?’” said Dr. Michael Hackett, ensemble trumpet player and professor.

At the time, African Americans had to use different bathrooms than white people, and didn’t receive financial support to attend school. These were just a few of the many rights not given to people of color. They wanted to be free in a segregated world. So they fought society’s oppression through music. They started taking gigs in clubs and they came up with a new style of music: bebop.

Mosaics Tribute to Charlie “Yardbird” Parker. (Mark Sheldon)

Bebop came out of the way music sounded, “ayba dooba dee bop bebop badoo,” and it’s intended to be listened to and improvised. Bird and Dizzy wanted to make music challenging, because it made it more difficult for the white culture to replicate their work.

“A lot of times the Black jazz musicians would come up with the blues, soul, and gospel elements. But then the white musicians who were trained in school, and had private teachers would go, ‘here are the Black musicians, steal their music and become really famous,’” said professional jazz musician Sharel Cassity.

They eventually got tired of the white culture stealing their music, so they decided to make something that no one else could play, and bebop was born. It was a combination between the blues and swing, really fast-paced, and a statement against racism.

“Listening is more important than anything. Not only do you have to read music, but you have to know the inner workings of music. As long as you know the style and the rhythm, anyone can play,” said Cassity.

The unique phrases had special meanings in jazz for African Americans because Bird and Dizzy couldn’t express their feelings verbally otherwise the whites would hear them. In their notes, there is a hidden language that is very meaningful, especially in the tone.

“Rather if it’s happy, sad or angry. The lines – are they aspiring – uplifting or more subdued,” said Cassity.

Recently Cassity produced her fifth jazz album Fearless, which was based on her journey from New York to Chicago. In the past, she produced 60’s jazz, contemporary, romantic jazz and an electric funk style. However, many musicians like Cassity went through many eye-opening experiences along their journey.

“One for me was a sustainable way to support myself, that comes from accepting certain realities. I asked myself, ‘What kind of student life do you want to live so you feel good?’ If I am not taking care of myself emotionally, physically or spiritually I can’t go out into public and be someone who can care about someone else,’” said professional drummer Devin Drobka.

Music helped him work on his happiness, because it made him become more present and secure about his current life. Happiness to him is if he can be aware of the small moments and decisions, without dwelling on his past.

“It’s listening to somebody: can I hear them, am I understanding somebody else, am I being understood by somebody else? Am I happy to brush my teeth in the morning?” said Drobka.

To him, happiness is about what he gives back to the community. And through this attribute, he discovered what he enjoys most, like teaching the drums to his jazz students.

“In a small jazz group, you’ll have a couple of horn players: the trumpet and saxophone ‘melodies.’ Then you have the rhythm section, which is the piano, bass, and drums. They function together as a unit and work to define the chords, rhythm and structure,” said Dr. Rob Hodson, a jazz pianist and music theory professor.

All these instruments work together and combine with the horns in real-time in jazz. The ensemble didn’t rehearse for their concert, but the unique thing about jazz is that as long as the musicians know the common style, they can instantly play with anyone. It was an improvised concert, just like Bird and Dizzy might have done.

Joyce Bezier • Mar 24, 2021 at 5:49 am

What an informative and well presented article. This had to have taken a lot of time and

research. Lizzy is one of the best writers I have ever read, and I read on a daily basis. My goodness,

this girl, sorry, young lady has great talent. A real gift. Way to go Lizzy!!!!