Did you know UW-W once had an Indigenous logo?

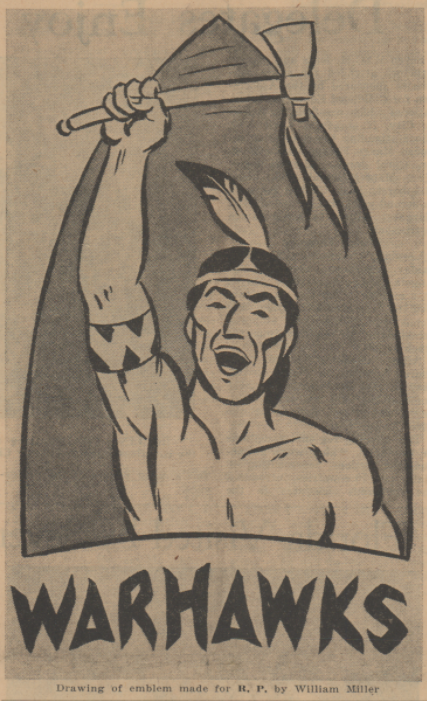

The Royal Purple does not condone the subject matter of the images used in this article. The images are solely for the purpose of learning from historical evidence.

The original Warhawks logo, first published in a Royal Purple September of 1972

February 13, 2022

The world is changing, but not everyone is changing with the world. Indigenous nicknames and logos have been in sports for a century, recently professional, collegiate and high school teams have ditched their Indigenous branding for less controversial ones. UW-Whitewater took this same step 50 years ago.

In 1958 the Royal Purple held a contest to adopt an official nickname and logo for the university to use, previously the athletic teams had been unofficially known as the “Quakers.” The contest resulted in the name that we know and love today, “Warhawks,” however, the logo was vastly different from our familiar bird logo today. That new logo was an image of an Indigenous person raising a tomahawk.

The name Warhawks was submitted by four students: August Revoy, Ron Hall, John Rabata and William Jolly. The four had different reasons for picking the name, ranging from it sounded good to thinking it would tie in well with the name of the university’s yearbook, “Minneiska,” which translates to Whitewater. Revoy and Rabata were quoted in an April 1958 Royal Purple issue saying that they had “thought of an eagle as the symbol for Warhawks instead of an Indian.”

“They talked about how the logo was historically appropriate. So they had their reasons,” UW-W archivist Jennifer Motszko said. “They believed they were honoring the traditions of Native American history by choosing a Brave to represent the school.”

When the new logo was announced in an April 1958 Royal Purple issue the paper stated that the image was “historically appropriate,” because “this is historically Indian country, the Warhawks seemed to be symbolic of the early fighting spirit possessed by the Indians in this area.”

The logo was unveiled in 1958 and remained the primary logo until 1972, however, the basketball floor in Kachel Gymnasium is known to have had the logo on the floor until 1983. The logo was not the only form of misuse in Indigenous imagery, cheerleaders dressed with feathers and even a mascot were seen at sporting events and parades.

“It is almost degrading them, and putting them on the pedestal because other sports teams and logos are usually fierce animals or things to be afraid of. It is dehumanizing them and taking away from them as a people really,” said Native American Support Services coordinator Michael Bose.

The logo was changed in 1972, amid a national trend of getting away from the use of Indigenous nicknames and logos.

“It really took getting into the 1960’s and 70’s when we have the Civil Rights actions and women’s rights, and all of this is starting to change so it seems rather timely when it started to happen,” Motszko said.

The change was one that may be expected to have been met with strong opposition. Today we see many examples of teams and their fan bases being very hesitant to change their Indigenous branding. However, according to Motszko the change was smooth. Another contest was held – this time in search of a less controversial logo.

“I think it seems like it went through pretty easily, as far as it was accepted that there was another contest that was going to do this,” Motszko said. “In the 60’s and 70’s there was so much going on. We [the university] were getting bomb threats, in 1974 we expelled some African American students – there was just a lot going on. I have a feeling that this wasn’t the thing that was upsetting people.”

Today, oftentimes when teams change their logo they also change their nickname along with it. In the case of Whitewater, the name Warhawks was retained and is in use now as a hawk rather than an Indigenous person. Unlike those other names, Warhawks is easily recognizable as being an animal.

“The way we have it now, it seems more like a bird instead of an Indigenous person. When I see Warhawk I’m assuming more like a hawk and not an Indigenous person,” Bose said.

“Warhawks actually makes complete sense that they switched to a hawk. Now when you look at it it’s like why were we ever something else,” said Motszko.

The first iteration of the hawk logo was revealed in a September 1972 edition of the Royal Purple. The change in Whitewater came nearly 50 years before the NFL team in Washington was financially pressured out of continuing to use a slur for Indigenous people as their nickname, which was in use since 1933.

“I think there has been a lot of social pressure on them to change. Them doing so is not going to change what they have done, but it’s good to not have that in our media anymore,” Bose said. “When you look at the team in Washington, that is one of the most offensive terms you can call a Indigenous person and that was a sports team for a very long time. I am glad they are getting away from it. It should not have been there in the first place.”

The idea of honoring Indigenous people through logos and nicknames is often brought up when discussing this topic. Bose, a junior majoring in political science, said it is practically impossible to honor in this fashion.

“I think it is pretty impossible. When we look at the situation, the majority of Indigenous people do not support it and are against that. The people you see backing it up are not Indigenous so I think we need to look at the people that it is actually affecting,” Bose said.

Currently there are still a number of high schools in the state of Wisconsin that use Indigenous nicknames and/or imagery. The closest is Fort Atkinson High School, which goes by the name of Blackhawks and uses an image of an Indigenous person wearing feathers. But the number of high schools, as well as colleges and professional teams using Indigenous nicknames and imagery has dwindled since the 1970s.

Today there are several organizations on campus such as Native American Support Services and the Native American Cultural Awareness Association, which work to help people – whether Indigenous or not – understand the culture and history of the Whitewater area.